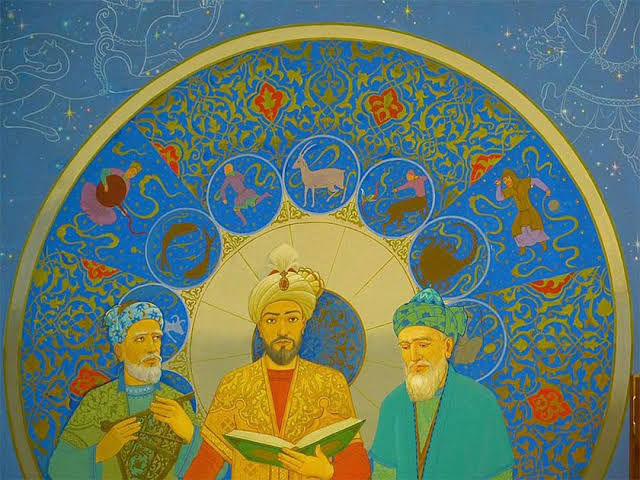

Mirza Ulugh Beg contributions in Astronomy

Ulugh Beg invented a mechanical planetary computer which he called the Plate of Zones, which could graphically solve a number of planetary problems; including the prediction of the true positions in longitude

Born into, Ulugh Beg gained fame for his intellect and pioneering strides in astronomy and mathematics. Ulugh Beg’s father Shahrukh was the fourth son of Timur and by 1407 A.D he had gained overall control of most of the empire, including Iran and Turkistan regaining control of Samarkand. In contrast to his grandfather Timur, Ulugh Beg’s vocation and passion was in science and arts. He was a musician, poet, philosopher, hafiz, and hunter and had a talent for astronomy and mathematics.

In 1409 A.D. Shahrukh decided to make Herat in Khorasan (today in Western Afghanistan) his new capital. Shahrukh ruled there making it a trading and cultural center. He founded a library there and became a patron of the arts. However Shahrukh did not give up Samarkand, rather he decided to give it to his son Ulugh Beg who was more interested in making the city a cultural center than he was in politics or military conquest.

Ulugh Beg was only sixteen years old when his father put him in control of Samarkand, he became his father’s deputy and he became ruler of the Mawara’u’n-nahr region

In 1417, to push forward the study of astronomy, Ulugh Beg began building a madrasah which is a center for higher education. The madrasah, fronting the Registan Square in Samarkand, was completed in 1420 and Ulugh Beg then began to appoint the best scientists he could find to positions there as lecturers.

Ex- South Korean President Moon Jae-in visited on April 20, 2019 the Ulugh Beg Observatory in the historical Uzbek city of Samarkand with Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev

As the Islamic calendar and prayer timings are linked to lunar movements, the first observatories started appearing in the Muslim world in the 9th century and coincided with a peaked interest for Muslims in astronomy and mathematics. There were several observatories from Cordoba and Toledo, to Cairo and Baghdad. Up until Ulugh Beg’s reign, hundreds of astronomers and mathematicians had already been produced in the Muslim world. The Maragheh observatory was one that had impressed Ulugh Beg, however. Since Jamshid al Kashi or kashaani and Qadi Zada al Rumi became his lecturers, Ulugh Beg’s conquests mainly focused on the sky, stars and planets, rather than on countries on earth.

During his reign, Ulugh Beg avoided war as much as he could, and spent nearly his entire wealth on art, science and cultural events

He also established his own observatory outside Samarkand on a rocky hill three stories high reaching a height of approximately 30m. It was one of the largest in the pre-modern era and was beautifully decorated with glazed tiles and marble plates.

The most remarkable instrument in Ulugh Beg’s there was the huge Fakhri sextant which boasted a radius of 40m, making it at the time, the largest astronomical instrument in the world of that type

The Fakhri sextant determines basic constants in astronomy: the inclination of the ecliptic to the equator, the point of the vernal equinox, the length of the tropical year, and other constants arising from observation of the sun. It was built chiefly for solar observations in general, and for those of the moon and the planets, too. The main reason behind the sextant’s success was the accuracy it gave due to its large size. On the arc of the sextant, divisions of 70.2 cm represented one degree, while marks separated by 11.7mm corresponded to one minute, while marks spaced only 1mm apart represented five seconds. Items known to have been used in Samarkand include astrolabes, quadrants, sine and versed sine instruments, as well as an armillary sphere, a parallactic ruler, and a triquetrum. The achievements of the scientists at the Observatory, working there under Ulugh Beg’s direction and in collaboration with him include the following: methods for giving accurate approximate solutions of cubic equations; work with the binomial theorem; Ulugh Beg’s accurate tables of sines and tangents correct to eight decimal places; formulae of spherical trigonometry; and of particular importance, Ulugh Beg’s Catalogue of the stars, the first comprehensive stellar catalogue since that of Ptolemy.

This star catalogue, the Zij-i-Sultani, set the standard for such works up to the seventeenth century. Published in 1437, it gives the positions of 992 stars. The catalogue was the results of a combined effort by a number of people working at the Observatory including Ulugh Beg, al-Kashi, and Qadi Zada. As well as tables of observations made at the Observatory, the work contained calendar calculations and results in trigonometry.

Under his leadership, observations also included the measurement of the obliquity of the ecliptic (angle between the celestial equator and the tropic of Cancer) as 23 degrees and 30’17” (the actual value at the time was 23 degrees and 30’48”) and that of the latitude of Samarkand as 39 degrees and 37’33” N. (modern value: 39 degrees and 40′). He measured the solar year in 1437, starting with the Spring Equinox at 365 days 5 hours, 49 minutes and 15 seconds – more accurate than Copernicus would later estimate. He determined the Earth’s axial tilt as 23.52 degrees, which remains the most accurate measurement to date.

The trigonometric results include tables of sines and tangents given at 1° intervals. These tables display a high degree of accuracy, being correct to at least 8 decimal places. The calculation is built on an accurate determination of sin 1° which Ulugh Beg solved by showing it to be the solution of a cubic equation which he then solved by numerical methods.

He obtained

sin 1° = 0.017452406437283571

The correct approximation is

sin 1° = 0.017452406437283512820

Showing the remarkable accuracy which Ulugh Beg achieved.

It is known that various well-known Muslim astronomers had worked there and some of the most extensive observations of planets and fixed stars at any Islamic observatory were made here.

Al-Kashi with the help of Ulugh Beg invented a mechanical planetary computer which he called the Plate of Zones, which could graphically solve a number of planetary problems; including the prediction of the true positions in longitude

Here are some results of a study of the yearly movements of the five bright planets known in the time of Ulugh Beg:

| Ulugh Beg Team Value | Exact Value in Modern Times |

| Mercury 530 43’ 13’’ | Mercury 530 43’ 3’’ |

| Venus 2240 17’ 32’’ | Venus 2240 17’ 30’’ |

| Mars 1910 17’ 15’’ | Mars 1910 17’ 10’’ |

| Jupiter 300 20’ 34’’ | Jupiter 300 20’ 31’’ |

| Saturn 120 13’ 39’’ | Saturn 120 13’ 36’’ |

Thus the difference between Ulugh Beg’s data and that of modern times relating to the first four planets falls within the limits of two to five seconds.

As it can be observed in the data, Ulugh Beg’s results are almost the same as those found through modern technology

He was one of the first to advocate and build permanently mounted astronomical instruments. Ulugh Beg was most certainly the most important observational astronomer of the 15th century. That he achieved all of this two centuries before the invention of the first telescope, speaks volumes of his talent and skill. Following a publication of the Latin version of his works in London, in 1650, he became known in Europe.

A museum called The Ulugh Beg Observatory was built in 1970 in Samarkand as a commemoration, and there one can view Beg’s Star Charts and the Zij-i Sultani.