Kazakh Language Past, Present and Future

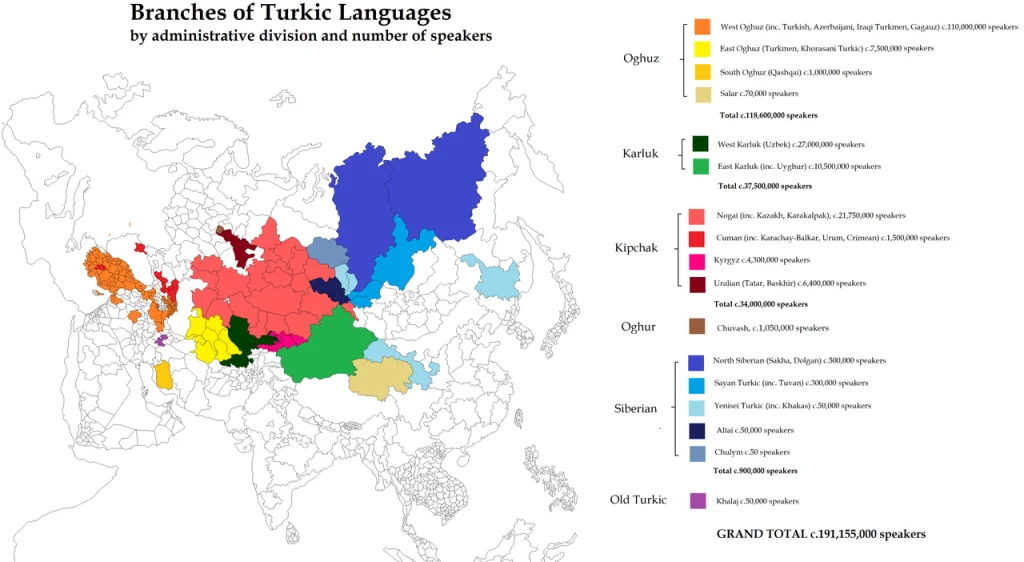

Kazakh language or (قازاقشا or قازاق تيلي (Arabic Script)) or Qazaq or qazaq tili is almost spoken by seventeen million people in Kazakhstan, as well as parts of China, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and the Russian Federation.

Though a proud member of the Turkic and Altaic family of languages, Kazakh has changed alphabets twice in the last hundred years, each change a reflection of Kazakh and its speakers’ uncertain and ever-changing identities.

Historical Past of the Kazakh Language

The modern Kazakh nation traces its roots to a loose confederation of Uzbek separatist tribes led by Janibek Khan and Kerey Khan, which broke away from the main Uzbek Khanate between 1456 and 1465 CE. They settled on the steppes that form much of modern-day Kazakhstan.

Under Janibek Khan’s son, Qasim Khan, the tribes were briefly united under one political entity known as the Kazakh Orda. However, after his death, they split into three large tribal federations or Hordes, called Jüz. The Ulu Jüz or Greater Jüz controlled the east and southeastern areas of modern-day Kazakhstan, the Kishi (Lesser) Jüz the southwest and between them the Orta (Middle) Jüz.

These Jüz, together with the Uzbek Khanate, initially spoke another language, Chagatay. Due to the split from the Uzbek Khanate, however, the language spoken in the Jüz began to change, acquiring new vocabulary and grammatical features. It eventually became recognized as a separate language known as Kazakh.

Initially, Kazakh was largely an oral language; little of it was written down, and when it was written down it was done so in the same modified version of an Arabic script used by Chagatay, which had been developed in the tenth century when Islam was introduced to the region.

Russian Era

In the early eighteenth century the Kishi and Orta Jüz came under the protection of Russia. At first, relations between the Kazakhs and the Russian Empire were amicable, with scientific expeditions mandated by Catherine II and the Russian Academy of Sciences making great inquests into eighteenth-century Kazakh society. However, by the mid-nineteenth century, the Russians had seized and incorporated all three of the Jüz into the Empire, ending four centuries of Kazakh independence.

The nineteenth century also saw the emergence of a standard form of written Kazakh in the Arabic script, with the emergence of an intellectual elite and the great Kazakh poet and writer Abay Qunanbayuli or Abai Kunanbaev (1845–1904), considered the founder of the modern Kazakh literary language.

In 1920, Kazakh territory was consolidated under the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR), which was renamed the Kazakh ASSR in 1925. It was around this time that the Kazakh language underwent its first orthographic change, with Soviet authorities switching it from an Arabic to a Latin-based script (using the same letters as English) in 1927. Then, starting in 1936, under Iosef Stalin, all other languages in the Soviet Union were made to switch their alphabets to Cyrillic, the alphabet used by the Russian language. Kazakh was no exception, and thus in 1940 again switched its alphabet, this time from a Latin script to Cyrillic, after only thirteen years.

In 1989, Kazakh was recognized as an official language of the Kazakh ASSR, and in 1991, Kazakhstan became independent following the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, Kazakh has still had to compete with Russian in the years that have followed. Russian was demoted to the official “language of inter-ethnic communication” of the Kazakh ASSR in 1989, but was again raised to the status of “official language” in independent Kazakhstan in 1995. It remains the language of choice when it comes to inter-ethnic communication within the country, as only about 60% of the population is fluent in Kazakh.

Present scenario of the Kazakh Language

Today, there are four major dialects of Kazakh, with three corresponding roughly to the southern, eastern and northwestern parts of the country, and a fourth dialect spoken in China’s Xinjiang province and Mongolia. The dialect used in the northwest of Kazakhstan is considered the standard variety of the language.

Kazakh, like all Turkic languages, is agglutinative – that is, it adds affixes to a word to express different grammatical ideas and relationships involving that word. In English, for example, you add the suffix ‘–s’ so you can talk about cats. However, where we would use a word like ‘with’ to describe an action in conjunction with the cat, for example, Kazakh adds a suffix ‘–pen’ instead: catpen (in our hypothetical Kazakhlish interlanguage).

You would think that after changing script twice in the same century, Kazakh would have had quite its fill of alphabetic alternation. Not so. In late 2006, Kazakhstan’s Ex-President Nursultan Nazarbayev established a government committee to study the possibility of swapping out the present Cyrillic-based script in favor of a Latin-based script. This committee returned in 2007 that with a draft implementation plan, a projected time period of fifteen years and an estimated cost of $300 million, but nothing more was heard about the topic until it was broached again by Nazarbayev in December 2012, who this time announced that the change would take place by 2025.

Why change? One reason is that a switch to a Latin script might lead to greater global integration for Kazakhstan. Global business, finance and science, as well as most influential businesses and media outlets, remain very much Western and thus Latin alphabet-dominated fields. A switch might implicitly signal Kazakhstan’s desire to be perceived as more current, modern and relevant—words.

It could also be because of new media. Already an unwieldy expansion of the less-widespread Cyrillic script, with eleven additional letters that are rarely supported by fonts and typefaces, Kazakh would arguably do well to make the jump to more oft-used Latin letters.

Quite naturally, any dramatic orthographic change has its opponents. In the case of Kazakh, many Kazakh intellectuals and writers have argued that a switch away from Cyrillic will render much of twentieth-century Kazakh writing inaccessible to future Kazakh generations. Kazakh may lose much of its literary history and identity as a result. The change will also require a massive civil undertaking, as not only newspapers and novels, but school textbooks, signs, street names and other quotidian features of the linguistic landscape will have to switch their letters.

Ex-President of Kazakhstan, Nazarbayev commented that the change had nothing to do with geopolitical reasons, a shift in alphabet could easily be read as a shift in political leaning, particularly if being perceived as more global also means being perceived as necessarily more Western. Moreover, where the Cyrillic alphabet has long-standing connotative associations with Russian in the Western world, the Latin alphabet is less readily identified with any one country, since unlike Cyrillic and Russia, there are a number of nations that use the Latin script and are major players on the world stage. A Latin alphabet might therefore give Kazakhstan room to develop its own identity independently from Russia.

Conclusion and Future

Ultimately, whatever Kazakhstan chooses to do with Kazakh will have interesting and far-reaching ramifications. A change in favor of Latin might motivate other former Soviet countries who had their scripts forced to Cyrillic to follow suit. On the other hand, the retention of Russian might instead suggest an understanding of the need to retain a link to the country’s (however recent) past.

The language reform is focused on modernization of Kazakhstan, especially utilizing language as one of the main driving forces of modernization. However, in my opinion, the future of the people of Kazakhstan lies in the fluent use of Kazakh, Russian and English languages. Only time and people of the Kazakh nation will tell where which set of letters the language of the Steppes throws its lot in with—or even if it will stay there.